About lake Dianchi: the green jade water colour

geographical location of the sub-tropical lake

Dianchi, 2000:

Dianchi, 2000:

View onto the

open lake in the south.

Dianchi, 2000:

Dianchi, 2000:

Farming in the man-made littoral zone close to the industrial zone at

the

lakeshore.

Lake Dianchi is the sixth largest freshwater lake in China. This shallow lake in the vicinity of the city Kunming, Yunnan province is located at 24°51’12.6'' N, 102°44’11.4'' E at 1888 m above sea level. The lake is divided into the inner lake close to the city in the north and the southern outer lake (or open lake).

eye-catching blue-green water colour in the northern part of the lake

Environmental pollution has many faces. Eutrophication is one face where an artificially high input of main nutrient elements as phosphorus and nitrogen affects an ecosystem. The concentrations of nutrients in an eutrophied lake are therefore, much higher compared to the natural background of an ecosystem is. High nutrient loads, e.g. by untreated waste-water inflow, generate an ‘extreme’ environment. Such a drastic environmental shift is usually responded to by the growth of only a few ‘specialized’ microorganisms that are adjusted to such a particular situation. In the case of eutrophication of lakes, these ‘specialized’ microorganisms are often aquatic cyanobacteria. The only alternate phytoplankton groups, which also occur commonly in but rather small water bodies, are the green algae (harmless chlorophyta).

Microcystis

in Dianchi Lake, 2000:

Microcystis

in Dianchi Lake, 2000:

Harbour in northern part of the lake at city Kunming, the eye-catching

surface scum of cyanobacteria is mainly of Microcystis.

.

Microcystis

in Dianchi Lake, 2000:

Microcystis

in Dianchi Lake, 2000:

Splashing water looks like beautiful pearls made from green Chinese

jade - but it certainly indicates a serious ecosystem health problem

due to an unwanted bloom of potentially harmful cyanobacteria.

Lake Dianchi has faced eutrophication problems for years. In particular, the northern part, close to the capital Kunming, cyanobacterial blooms occurred during the growing season as shown in the photo gallery above in years 2000 and 2001. The splashing water behind a motor craft looked like beautiful pearls made from green Chinese jade! Unfortunately, the coloured water indicated a serious ecosystem health problem, namely an unpleasant bloom of potentially harmful cyanobacteria in Dianchi.

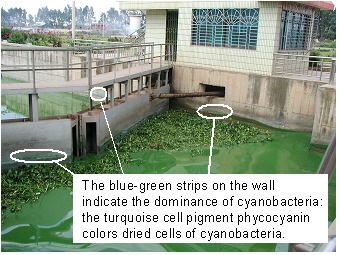

Microcystis

in Dianchi, the north of the lake, 2000:

Microcystis

in Dianchi, the north of the lake, 2000:

In addition to the bloom of cyanobacteria in the water,

plants of water hyacinth are

accumulated at this ship lock.

Microcystis

in Dianchi, the north of the lake, 2000:

Microcystis

in Dianchi, the north of the lake, 2000:

The blue strips indicate cyanobacteria which are dried out due to water

level fluctuations.

Microcystis

in Dianchi, the north of the lake, 2000:

Microcystis

in Dianchi, the north of the lake, 2000:

The blue strips on the wall indicate cyanobacteria in the neighborhood

of the housing area.

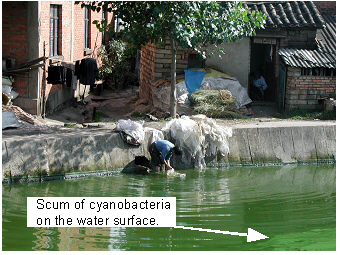

Microcystis

in Dianchi, the north of the lake, 2000:

Microcystis

in Dianchi, the north of the lake, 2000:

On a calm day, the cyanobacterial cells being alive are able to

stratify at a

very narrow top surface layer, while the lake bottom layer is almost

free of these micro-organisms.

The popular science name of the cyanobacterial microorganisms is ‘blue-green algae’. The name ‘blue-greens’ relate to pigments occurring specifically in cyanobacteria, namely the turquoise photosynthetic pigment phycocyanin (Teubner & Greisberger 2007 R; see pigments described for cyanobacteria in this website for Mondsee S and Taihu S). In the case that the cyanobacterial cell material dries out e.g. on stones of the shoreline due to water level fluctuations, the green chlorophyll is rapidly degraded in the dead cells while ‘blue’ phycocyanin still remains and becomes unmasked from green chlorophyll. Dry cyanobacteria can be hence easily identified by the blue colour. The ‘blue greens’ are, however, no photosynthetic algae but photosynthetic bacteria, and might be hence called cyanobacteria or cyanoprokaryotic microorganisms. Many of them are typical summer and early autumn species, most common in nutrient-rich lakes around the globe (Dokulil & Teubner 2000 R).

A cyanobacterial scum is in particular seen on a calm day, and is an obvious warning signal of a health risk (surface scum seen also on Taihu and Mondsee). The stratification of such a blue-green bloom at the water surface can be achieved by the buoyancy regulation of cyanobacterial cells (see further Mondsee).

Dianchi, 2000:

Dianchi, 2000:

Lift net operated on the lakeshore.

Dianchi, 2000:

Dianchi, 2000:

Lift net operated on the fisher boat. The net is just lifted up to look

for

the fish catch. Further details about lift nets and wooden

fishermen boats are described on websites about Yichang S and Shennong Xi

S,

which are both tributaries of the Yangtze River S)

Dianchi, 2000:

Dianchi, 2000:

Same as above right photo but lifted net down.

Dianchi, 2000:

Dianchi, 2000:

Traditional fisherboats on the lake.

The photosynthetic micro-organisms floating in the water body of a lake, called phytoplankton, are the main food source for many non-photosynthetic organisms from bacteria to small planktonic animals and fishes in a lake. The greater the variety in the phytoplankton assemblage is, the more diverse is the food quality. Some animal feeders just incorporate food particles of a certain size range by filtration while other are even able to select the preferred food. In the case of a cyanobacterial bloom of phytoplankton, the diversity of food declines to a few taxa only. Further, some of these cyanobacteria are known to build toxins that may affect the health of feeding organisms in the ecosystem but also human health via the consumption of drinking water and food harvested from such a cyanobacterial lake. Therefore the growth of these cyanobacterial micro-organisms might be controlled. by a drastic reduction of the nutrient load, achieved best by an effective sustainable restoration management in the catchment of a lake, in advance to in-lake restoration treatments.

Dianchi, lake management,

2000:

Dianchi, lake management,

2000:

In-lake plantation of water hyacinth (Eichornia

crassipes) in framed

constructions. This lake management regulation aims at removing

nutrients from the lake water by the growth and harvest of the biomass

of this plant.

Dianchi, lake management, 2000:

Dianchi, lake management, 2000:

Same as the left photo but showing a larger area of the plantation.

Dianchi in the north at the city

Kunming, 2000:

Dianchi in the north at the city

Kunming, 2000:

Water hyacinth (Eichornia

crassipes, originating from in-lake plantations), Lemna and a surface scum of

cyanobacteria are seen on the shallow lakeshore.

Dianchi, 2001:

Dianchi, 2001:

Not only water hyacinth but also other aquatic macrophytes are

planted in an artificial littoral zone to remove nutrients controlling

the

phytoplankton growth, to function as habitat for aquatic animals from

zooplankton to molluscs and fish and even to serve the fishermen as

bait traps (see on this website shrimp bait for traps on lake Taihu S).

Planting water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) is an in-lake restoration treatment seen in this sub-tropical lake Dianchi. Growing water plants, indeed, is a common powerful bio-manipulation method successfully applied in many lakes, in particular, in the case when other initial restoration methods of catchment restoration were applied in advance and an ongoing reduction of the external nutrient load is already achieved.

Lake eutrophication is not a regional but a common phenomenon in urban regions around the globe. Examples on this website, which describe in particular lake-periods of eutrophication and restoration are the shallow lakes Old Danube S, Grosser Mueggelsee S and Taihu S and the deep lakes Mondsee S and Ammersee S .

Further it is worth mentioning here, that aquatic cyanobacteria are not in general producers of toxins. Some cyanobacteria are not toxic at all. Some forms of cyanobacterial genera, Spirolina and Noctoc for example, are even used as a food supplement for healthy nutrition or can be simply served as a dish for lunch (see page cyanobacteria on site 'Lab Views').

cited References on this site about dianchi

Greisberger, S. & K. Teubner. 2007. Does pigment composition reflect phytoplankton community structure in differing temperature and light conditions in a deep alpine lake? An approach using HPLC and delayed fluorescence (DF) techniques. J Phycol, 43, 1108-19. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00404.x Look-Inside FurtherLink

Dokulil, M. & K. Teubner. 2000. Cyanobacterial dominance in lakes. Hydrobiologia 438: 1-12 Abstract FurtherLink