Über den

Shennong

Fluss:

ein Gebirgsstrom, der in den Jangtsekiang fließt

geographische lage des baches

Shennong Strom, 2004:

Shennong Strom, 2004:

Ein typisches Stimmungsbild vom Strom – leise gleiten kleine

traditionell-chinesische Holz-Planken-Boote ('sam pans') den Strom

entlang. Das

gleichmäßig-ruhige Plätschern durch das rhythmische Bewegen der Ruder

und Stakstangen ist kaum zu hören. Diese kleinen Boote

werden umgangssprachlich auch als "peapod boat", d.h.

als "Erbsenschale" oder "Erbsenhülse" bezeichnet.  Shennong Strom, 2004:

Shennong Strom, 2004:

Ein typischer Landschaftsblick vom Strom nahe seiner Mündung

in den Jangtsekiang - der Strom schlängelt sich im Tal zwischen

abgerundeten Bergkappen entlang. Das Wasser sieht gelblich-grün gefärbt

aus. Die Wasserfarbe ergibt sich nicht etwa durch die Wasserspiegelung

der angrenzenden grün-bewaldeten Berghänge, sondern resultiert primär

aus den vermehrt auftretenden photosynthetischen Mikroorganismen im

Wasserkörper, wie z.B. den Algen.

Der Shennong Fluss (Shen Nong Xi, Shen Nong Fluss) ist ein Nebenfluss vom Jangtsekiang. Die Mündung dieses Gebirgsstroms liegt in der Nähe der Stadt Badong (31°02’ N 110°20’ E) 381 m über dem Meeresspiegel, in der Enshi Tujia und Miao Autonomen Präfektur der Provinz Hubei. Der Shennong Fluss ist etwa 60 km lang. Im Jahr des Besuches, 2004, machte der schiffbare Teil etwa ein Drittel der Länge des Gebirgsstroms aus. Die malerische Landschaft, die Relikte historischer Besiedlungen (z.B. die in den Felsenspalten hoch oben hängenden Särge) und die gegenwärtige Tradition der an diesem Fluss lebenden Menschen stellen den Shennong als eine Attraktion für Touristen aus dem In- und Ausland heraus (siehe Galeriefoto 9). Besucher, die den Shennong Fluss entlang fahren, müssen in kleinere Motor-Ausflugsschiffe umsteigen, weil die riesigen Jangtsekiang Kreuzfahrtschiffe das schmale Shennong Bachbett nicht passieren können. Die kleineren Ausflugsschiffe fahren den Strom etwa 20 km von der Mündung weg in eine Gebirgslandschaft hinein. In einem kleinen Hafen, der am Ende des schiffbaren Abschnittes liegt, wechseln dann die Reisenden von dem Schiff auf kleine Boote. Die Bevölkerung vor Ort bietet hier nämlich an, den Gebirgsstrom weiter flussaufwärts mit traditionellen, flachen Holzbooten befahren zu können. Diese Boote werden zuerst rudernd bewegt, später stakend oder sogar treidelnd durch das sich weiter verengende und auch zunehmend flachere Gebirgsbachbett (siehe Galeriefotos 12 und 13).

Mit dem Bau des Drei-Schluchten-Staudammes war im Jahr 2004 der Wasserspiegel im Jangtsekiang S und damit auch in seinen von dem Damm flussaufwärts gelegenen Nebenflüssen bereits um einige Meter angehoben worden. Die Wasserstandsmarkierungen, die am Jangtsekiang zeitgleich mit dem Besuch am Shennong Xi fotografiert wurden, zeigen an, dass der Wasserstand mit der Fertigstellung des Dammes um weitere 70 Meter steigen soll. Viele auf dieser Shennong Xi Webseite gezeigten Uferstellen werden damit heute in der Form nicht mehr existieren und unter der Wasserlinie liegend dauerhaft geflutet sein.

Auf dieser Webseite wird der schiffbare Abschnitt von etwa 20 km (10 bis 20 km?) in der Nähe der Mündung in den Jangtsekiang Fluss sowie eine weitere kurze Strecke von dem eigentlich schmalen Gebirgsbach beschrieben. Anders als das gelb-braun erdige Wasser vom Jangtsekiang ist das Wasser des schiffbaren Abschnittes vom Shennong aufgrund einer recht massiven Phytoplanktonentwicklung intensiv gelblich grün gefärbt. Stromaufwärts von der Stadt mit dem kleinen Hafen geht der Strom in einen schmalen kristallklaren Gebirgsbach über. Der sich ändernde Charakter dieses Stromes – nämlich der Wechsel von einem klaren steinigen Gebirgsbach im Oberlauf zu einem algen-grünen schiffbaren Strom nahe der Mündung – wird detaillierter in dem nachfolgenden Text beschrieben.

the changing nature along the downward

flow of the stream:

the different faces of shennong xi.

The words of the idiom ‘panta rhei’ refer to the flow of a river (in German ‘Alles fliesst/Alles ist im Fluss’) with the meaning that ‘everything changes' or 'everything is in progress’. Indeed, ecosystem changes can be identified along the downward flow of a river channel: from the mountain highland to the mouth, where the stream joins into a larger stream or river or into a lake or ocean. As the landscape changes adjacent to the stream, also the character of the streambed, the oxygen concentration, temperature, flow velocity, turbidity and nutrient level alter. Further, in accordance to this changing environment, the habitat conditions and hence adjusted biotic communities alter successively. In contrast to floating microorganisms, which are mainly passively drifted with the downward flow, larger animals can move and therefore, stay in a certain stretch preferred to live. Key species of fish communities are thus commonly used to describe particular zones of habitat conditions of a stream (zonation of a stream). Ecologists are describing the complexity of biotic life in a river system and the connected floodplain by a numerous of concepts, which are not explained at all here. As the main focus of the lakeriver-website is on algae in water basins, the zonation of the Shennong stream will be only discussed with respect to the water color and the development of phytoplankton, i.e. in the water floating or drifting photosynthetic micoorganisms.

Gebirgsstrom Shennong,

2004:

Gebirgsstrom Shennong,

2004:

Das Wasser sieht kristallklar aus.

Gebirgsstrom Shennong, 2004:

Gebirgsstrom Shennong, 2004:

Stromschnellen im flachen steinigen Bachbett.

Gebirgsstrom Shennong,

2004:

Gebirgsstrom Shennong,

2004:

Weiter stromaufwärts prägen steile Felswände und

Gebirgsquellen ('mountain springs') das Bild vom Bachbett. Die

türkis-blaugrüne Farbe

ergibt sich allein durch die optischen Eigenschaften des Wassers und

nicht durch Mikroorganismen wie Algen in eutrophierten, d.h.

nährstoffreichen, Gewässern (siehe auch den tief türkis gefärbten

Wasserkörper im alpinen Traunsee S

auf dieser lakeriver-Webseite).

Gebirgsstrom Shennong, 2004:

Gebirgsstrom Shennong, 2004:

Detailansicht auf die felsigen Hänge am Bach.

The four photos above are from the highland mountain stretch of the Shennong stream. The water tumbled over rocks and stones of a shallow river bed and looked crystal clear. Mountain springs could be commonly seen on the rocky shore. At steeper holes, the deep water looked turquoise-blue. This colour was just due to optical properties of the water, not due to ‘blue-green algae’, the cyanobacteria. Another water basin with deep-turquoise coloured water described on the lakeriver-website is the alpine lake Traunsee S in the Austrian Alps. In that oligotrophic, i.e. nutrient-poor lake, the rather blue-milky water colour is also not due to phytoplankton, but due to suspended solids from the mountains.

Primary producers, such as planktonic algae and cyanobacteria, cannot grow well in the rapidly flowing headwater for many reasons. Due to the strong current running, the growth of cells of primary producers is inhibited by mechanical stress. Furthermore, the nutrients needed for phytoplankton growth are insufficiently available in the headwater. The bordering landscapes are rocks where no or only a thin layer of soil is on the surface. Thus, after rainfall, the water does NOT receive larger amounts of nutrients simply by soil erosion. Moreover, the steep rocky slopes at the headwater seemed to be unsuitable, not a favourite place for housing and farming at the Shennong stream. Accordingly, the anthropogenic impact of a nutrient increase played certainly no role on this stretch. The stony stream bed and biota found there are illustrated in the photos below.

Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

1997:

Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

1997:

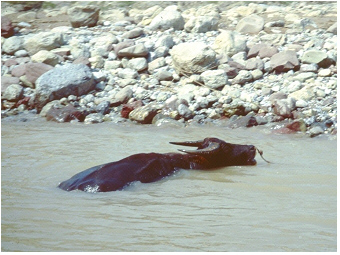

Dieses Foto wurde als einziges aus einer Fotoserie von diesem Strom aus

den späten neunziger Jahren ausgewählt. Bevor der Wasserstand mit dem

Bau des Drei-Schluchten-Dammes angehoben wurde, sah man häufig solch

eine

Fluss-Szene: Ein Bauern lässt hier seinen Wasserbüffel im seichten Ufer

baden. Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

2004:

Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

2004:

Steine in verschiedenen Größen wurden auf den flachen Ufern dieses

Gebirgsbach gefunden. Das Bachbett ist Lebensraum für viele Tiere, wie

z.B. für Vertreter vom Makrozoobenthos. Nach dem Hochheben der Steine

sind diese Tiere leicht zu entdecken.

Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

2004:

Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

2004:

Studentische Exkursion der Universität Wien, die von chinesischen

Kollegen organisiert wurde: Probenahme im seichten Bachbett und auf den

Schotterbänken. Eingefügtes Detailfoto: Kopf des Insekts Miomantis. Das Insekt

wurde auf den Steinen am Ufer gefunden.

Gebirgsfluss Shennong, 2004:

Gebirgsfluss Shennong, 2004:

Die Tiere, die das steinige Bachbett hier besiedeln, sind z.B. Larven

von Insekten und Muscheln (Corbicula

flumine). Während der

Studentenexkursion wurden sämtliche Tiere lebend gesammelt und nach der

taxonomischen

Bestimmung vor Ort sofort wieder an ihrem Fundort ausgesetzt.

Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

2004:

Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

2004:

Fische an diesem flachen und steinigen Bachabschnitt.

Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

2004:

Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

2004:

Weitflächige Schotterbänke sind stromaufwärts an flachen Uferstrecken

dieses Gebirgsbaches verbreitet. Die Bauarbeiten des

Drei-Schluchten-Staudammes waren in jener Zeit zugange. Mit der

Fertigstellung des Dammes werden diese flachen Stromstrecken dauerhaft

geflutet sein (siehe Details im obersten Textabschnitt).

Going further downward with the flow, the current is reduced and thewater meanders across valleys of less steep slope. In the case of the Shennong stream, the stream became wider and deeper at a larger town or city, the place where the habour for cruise ships was as the navigable stretch ended here at that time of the visit in 2004. Both, the lower current by meandering (longer retention time of water in a stretch) and the increase of nutrients (loaded from the bordering landscape) support in general the growth of phytoplankton in a stream. While a stream turns from a headwater to a downstream stretch, drifting algae still live on the ‘edge’. The water looks yet almost crystal-clear due to the lack of mass development of phytoplankton. The aspects of the limited development of phytoplankton near the headwater will be discussed in greater detail in the following paragraph.

In stretches of turbulent water flow, floating photosynthetic

microorganisms can only grow in shore areas separated from the main

stream, i.e. in niches such as small bays and cavities, where algae are

not rapidly washed out. The retained algae in such small niches need to

utilize nutrients. These nutrients, mainly compounds of phosphorus and

nitrogen, are replenished naturally from the geological background,

e.g. by soil erosion from the bordering valleys - or in the case of

Shennong Xi also from farm land. Algae then grow, i.e. they accomplish

at least one cell division. In case the

rate of cell division is higher

than the washing out rate, and grazing does not reduce

algal biomass

afterward, the phytoplankton organisms can succeed over several days to

a few weeks. The phytoplankton of such niches becomes introduced to the

main stream channel only by elevated water level, e.g. after flood

events such as heavy rainfalls. In case the demand for nutrients by

algae is higher than the supply/replenishment from the environment, the

algal growth becomes controlled by nutrients. This situation of low

nutrient load is typically found when rocks rather than

valleys and

soil are covering the stream bank, and no farmland is bordering the

stream. Under such nutrient-limiting

growth conditions, algae usually

need much more time to accomplish cell division and thus to increase

their biomass compared to an unlimited growth in nutrient-rich waters

much further downstream. The scenario of the growth of non-attached

algae in a stream (some forms of other algae are attached to stones in

the streambed, what are not considered here at all) is herewith just

described in a simplified form. It might give a rough idea about

phytoplankton development in a headwater that goes over into a

downstream stretch. The mutual

adjustment of algae and their

environment (other biota, physical and chemical

conditions), which

implies that algae are enabled to respond rapidly to environmental

modifications, however, is more complex and actually matches rather the

life in nature than the paraphrased description before.

Going further downstream, the deeper and wider streambed increasesconsiderably the retention time of the water, and the stream receives usually more nutrients from tributaries and bordering landscape than upstream. Reduced flow and an enhanced nutrient availability allow algae to accomplish cell division and thus to achieve growth while drifting in the stream channel. Actually, in view of phytoplankton growth, this stretch might remember a ‘steady-state flow’ as known from algal growth experiments in the lab. The increased biomass of floating photosynthetic microorganisms colours the water yellow-green as indeed seen on most photos of the navigable stretch across the Shennong stream. The photos 1-3 and 6-7 in the gallery, the two photos shown in the section about the geographical location and the two photos below indicate this green colour caused by phytoplankton. Even the water transparency is reduced due to the floating algae; sufficient light for photosynthesis penetrates the channel at least at a wider surface layer of the stream. In particular, species that can adjust to low light intensities in a turbulent water body, grow well (see adjustment of photosynthesis described for phytoplankton in alpine lake Traunsee, S on the lakeriver-website). Depending on the water retention time, it is not only the watercolour and the phytoplankton composition but also the whole ecosystem that changes. With increasing retention time of water, the ecosystem of a river turns to a riverine lake and finally to a lake as described for lake Grosser Mueggelsee, S on the lakeriver-website.

Shennong Fluss, 2004:

Shennong Fluss, 2004:

Schiffbarer Abschnitt stromabwärts, aber mit noch recht

steilen, felsigen

Uferhängen. Die Felsen sind von einer natürlichen Gebirgsvegetation mit

Bäumen und

Sträuchern bedeckt. Das Wasser sieht grün gefärbt aus. Shennong Fluss, 2004:

Shennong Fluss, 2004:

Dieser Stromabschnitt liegt bereits sehr nahe der Mündung in den

Jangtsekiang. Bauern bewirtschaften hier die Ufer bis zur Wasserkante

hinunter. Zum Teil sind terrassierte Felder angelegt. Das Wasser sieht

grün-bräunlich gefärbt aus. Eine suspendierte Partikelmischung liegt im

Wasser vor, nämlich aus eingeschwemmtem Bodenerosionsmaterial und sich

im Wasser vermehrenden Algen.

Jangtsekiang und

Badong, 2004:

Jangtsekiang und

Badong, 2004:

Die Stadt Badong liegt am Jangtsekiang Fluss, nahe der Mündung vom

Shennong Strom. Typischerweise sieht dieses Flusswasser allein

bräunlich

gefärbt

aus. Eine stärkere Algenentwicklung bleibt hier aufgrund der

Wachstumshemmung im Fluss aus, was im Text näher beschrieben

wird. Die Touristenkarte zeigt

die Attraktionen

und Städte in der Flussebene vom

Jangtsekiang. Sie war auf einem Kreuzfahrtschiff 2004 ausgehangen.

Die Touristenkarte zeigt

die Attraktionen

und Städte in der Flussebene vom

Jangtsekiang. Sie war auf einem Kreuzfahrtschiff 2004 ausgehangen.

Close to the mouth into the Yangtze River, the water of Shennong Xi looks brownish green due to enhanced concentrations of suspended solids (silt) in addition to floating green cells of primary producers. The muddy water colour is due to soil erosion from the bordering landscape, here often used for farming (see photo above, taken at city Badong). The crops are grown on the slopes on Shennong Xi even close down to the water's edge, in some areas on terraced fields. The same was found for the Yangtze River S, where the water colour looks just brown without a greenish tone.

The muddy water is nutrient rich and hence might support algal growth. Furthermore, water current is reduced in wider streambeds, which in addition might promote phytoplankton development. The low transparency of the water, however, provides insufficient light for photosynthesis. Thus, the huge amount of nutrient has, in principle, the enormous potential for an algal bloom, but cannot be utilized by algae drifting in the muddy stream or river. The dissolved nutrients are accumulated in the water while transferred further downstream. Entering a broad basin as a lake or a reservoir, the suspended solids of the river water deposit rapidly to the bottom (sediment layer) and thus the water transparency significantly increases. This scenario of improved underwater light climate allows phytoplankton growth. Within a few days, the water colour changes to green as one cell division per day (daily growth rate = 0.693 d-1), i.e. the doubling of phytoplankton biomass per day, can be easily accomplished during an initial nutrient-unlimited growth phase even in a natural habitat (algal growth rates of nutrient-addition experiments in the lab can be much higher). Planktonic blooms of cyanobacteria in lakes, which were mainly due to nutrient-rich inflows (!) are described on the lakeriver-website for a number of shallow water basins such as the lakes lake Taihu S, Dianchi S and Grosser Mueggelsee S. In the Meiliang Bay of the north of lake Taihu, were two tributaries join into the lake, the algal biomass measured by chlorophyll-a concentrations is significantly higher than at the centre of Taihu (Fig. 5 in Chen et al. 2003 R). More interesting within the context stated before is, that measurements of total phosphorus and also for total nitrogen close to the mouth where the Lujiang River joins into Meiliang Bay, were statistically significant higher than at any sampling station in Meiliang Bay or the centre of the lake (see map of sampling sites in Fig.1 in Chen et al. 2003 R). Despite the nutrient-rich situation of the inflow river water, the chlorophyll-a concentration is lower than measured at the two sites in the bay (Bay 1 and B2) in the close neighbourhood of this mouth (see annual averages for nutrients and chlorophyll-a at ‘M2’ for the mouth of Lujiang River and for the sites ‘B1&2’ in the Meiliang Bay Fig.2 in Chen et al. 2003 R). The enormous potential for an algal bloom by nutrient-enrichment in the river water became just obvious when entering the large shallow basin of the lake bay. A scum of cyanobacteria was built up during the growth season in the Meiliang Bay in Taihu.

take the chance going by boat upstream shennong xi

Gebirgsstrom Shennong,

2004:

Gebirgsstrom Shennong,

2004:

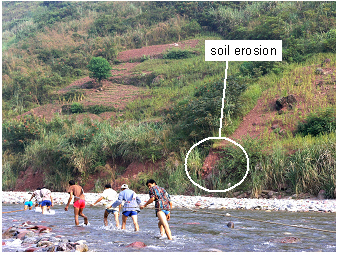

Männer (Treidler) ziehen die Boote stromaufwärts über einen flachen

Abschnitt eines erweiterten Bachbettes. Am steilen Uferhang sind

bestellte Felder zu sehen. Weiters ist Bodenerosion am Ufer auf dem

Foto zu erkennen. Sowohl die gängige Praxis der Bauern die Felder

hinunter bis zur Wasserkante zu bestellen und die frische Bodenerosion,

zeigen eine jüngste Flutung des Bachbettes an. Der Wasserstand erhöhte

sich zur damaligen Zeit sukzessive im Zuge der fortschreitenden

Fertigstellung des Drei-Schluchten-Dammes.

The photos of the Shennong stream shown on this website were mainly

taken in 2004, when the

Three Gorges Dam has been under

construction aimed at bringing up the water level to

175 m

(see the

water level mark the website about Yangtze

River S).

At that early

stage in 2004, the water level of Yangtze River had been already

increased by about 70m. The damming up of Yangtze River would also have

affected its tributaries: some old/ancient habitats have been

certainly lost, other

young habitats will be established with time. The elevation of the

water level

and water fluctuation definitely alters an ecosystem like the Shennon

Xi. In case of a scenario of further anthropogenic nutrient

enrichment, however, it might have a greater impact on such an

ecosystem.

As described in the introduction for Shennon Xi, the stretch

of the 'mountain stream' can only be passed by boat as in sections of a

stony streambed, the flow becomes shallow, while on other sections the

streambed is deep but very narrow. Local people were busy to organize

the tourist attraction of boat hauling or tugboat. The temperature

in an upstream section fed by springs is usually much lower than

upstream.

The visit

was in September, early autumn at Shennong Xi. People who were not

wading through the water, who were just waiting on the shore for

tourists or selling local goods were wearing long trousers. The

'boat haulers' or 'boat tuggers' preferred to wear long-sleeved shirts

due to the chilly

weather and cold water in the mountain stream.

Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

2004:

Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

2004:

Flache Holzboote sind für das Treideln im flachen steinigen Flussbett

geeignet. Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

2004:

Gebirgsfluss Shennong,

2004:

Ein Fischer kann sogar allein das Boot zugleich rudern und lenken: das

kurze seitliche Ruder dient der Vorwärtsbewegung und wird von der einen

Hand geführt, das längliche Ruder am Ende vom Boot dient der Steuerung

mit der anderen Hand.

Gebirgsstrom Shennong,

2004:

Gebirgsstrom Shennong,

2004:

Männer schleppen (treideln) stromaufwärts die kleinen Boote mit

Touristen über eine flache Strecke des Bergbaches. Gebirgsstrom Shennong, 2004:

Gebirgsstrom Shennong, 2004:

Gleiche Stelle vom Bach wie auf dem Foto links, aber eine Bootsfahrt

stromabwärts.

Gebirgsstrom Shennong,

2004:

Gebirgsstrom Shennong,

2004:

Wasserschöpfen aus dem flachen Boot mit Hilfe einer hölzernen

Wasserschaufel.

Gebirgsstrom Shennong, 2004:

Gebirgsstrom Shennong, 2004:

Detail der Konstruktion eines traditionellen Holzbootes zum Treideln

durch ein seichtes Bachbett. Der fest mit dem Bootsboden verankerte

kurze Mast, der hier am linken Bildrand zu sehen ist, dient dem

Befestigen des Seiles zum Treideln. Das Seil wird beim Treideln meist

über eine Astgabel oder Narbe am Holzmast oben straff entlang geführt

(siehe Foto links).

The wooden boats seen on the photos above were used as fisher boats and to transport goods and people as tourists. These flat-bottomed boats had a broad bow and slim stern. A varying number of oars, which were fixed on the side planks of the boat, was used to row the boat. An elongated oar with blade on the rear end was operated to steer. As seen on the photo below, even an individual person could handle well both simultaneously, to row and steer the boat S. The boats, which were, in particular, used for hauling to pass the shallow streambed, had in addition a stump of mast, which was made in its simplest form just by a stock of a tree. While hauling the boat, a rope was guided through the slot of this short mast. On a shallower stretch, also bamboo sticks were used to punt the boat. Some boats had permanent shelters on board, others just a simple cover to protect from rain and sunshine. Another, but a similar type of wooden fishing boats can be visited on the lakeriver-website for the stream Huangbai at Yichang S. These boats have shelters, which were permanently used on the boats. The fishing boats in Yichang were further equipped with a lift net S. This type of small wooden boat is depicted as a sampan or sam-pan (locally called 'peapod boat'), which describes literally the use of only three wooden planks to make a boat. Actually, more than three planks made the boats on Shennong Xi and Yichang. A more original type of such a boat, however, can be visited on the website about lake Dianchi S. The front view of a one fisherman boat with operating lift net may rather convey the idea that a boat can be simply made by three planks: one for the bottom and the other two on each side S.

cited References on this site about Shennong Xi

Chen, Y., Qin Boqiang, Teubner, K. & M. T. Dokulil. 2003. Long-term dynamics of phytoplankton assemblages: Microcystis-domination in Lake Taihu, a large shallow lake in China. J Plankton Res, 25 (1), 445-53. Abstract Abstract in Chinese OpenAccess

Chen, Y, Chengxin Fan, Teubner, K. & M. T. Dokulil. 2003. Changes of nutrients and phytoplankton chlorophyll-a in a large shallow lake, Taihu, China: an 8-year investigation. Hydrobiologia, 506: 273-79. Abstract OpenAccess