Hallstätter See: Ein tiefer Salzberg-see umgeben vom prähistorischen Hallstatt & keltischer Kultur

die geografische Lage des Sees in den österreichischen Alpen

Alpiner Hallstätter See, 2000:

Alpiner Hallstätter See, 2000:

Blick vom Wanderpfad „Ostuferweg“ nordwärts auf den See.

Der Hallstätter See (47°34’26.8''N,

13°39’26.3''E)

ist

ein

alpiner See im Salzkammergut

in

Oberösterreich (Österreich),

der 508 m über dem Meeresspiegel liegt. The lake basin area is

8.6 km2,

the water volume 557 x 106 m3

and the maximum depth 125 m. The lake has an elongated shape,

which extends over a distance of about 8 km from north to

south. The deep lake belongs to

the same

catchment

as lake Traunsee.

The theoretical

water retention time of Hallstätter

See is a half-year only (Table

1 in Dokulil & Teubner

2002 R,

Table 1 in Dokulil et

al.

2006 R)

. This is even shorter than for lake Traunsee, having about a four

times higher lake water

volume than Hallstaetter See. As described for lake Traunsee, the

reason

for the particular short water retention despite the large size of deep

alpine water basins is the large discharge of the river

Traun, which

flows through both lakes.

Alpine lake Hallstaetter See, 2001:

Alpine lake Hallstaetter See, 2001:

View southward onto the lake elongated between north and south. In the

back, on the west bank of the lake, the town Hallstatt can be seen.

The water retention time of large deep lakes,

however, is usually much longer, as already discussed on the website of

lake Traunsee

S

comparing Traunsee and Mondsee. Mondsee S

has about

the same water volume (510 x 106

m3)

as lake Hallstätter See, is also located in the Salzkammergut district

in Upper Austria but in the neighbouring catchment and has a

theoretical water retention time of 1.7 years. Lakes of very

short

water retention lasting from days to a few months are typically flushed

shallow lakes in lowland river-floodplains and are called 'riverine

lakes' S

and hence have a quite different limnology compared to that of

deep alpine

lakes.

The Hallstatt area is an

ancient place. The importance

of Hallstatt is mirrored in the eponymously named period of

Early Iron Age

(

‘Hallstatt’ culture). This populated site is also rich in

Late Iron

Age history (

‘Celtic’ culture). Palaeolimnological studies on sediments

of lakes in this alpine region describe very well the impact of climate

and

land use for this mountain area from these prehistoric periods until

recent times (see e.g. Schmidt et al. 2008 R

& 2009 R).

The medieval town Hallstatt

is located in the south of the

west bank of the lake. According to descriptions by Simony in 1866/67

(see page 51

in Grims 1996 R),

all

early morning many salt miners travelled in wooden barges

(boats) on lake Hallstaetter See to Hallstatt, and were then hiking

the

mountain Hallberg (Salzberg at Hallstatt) via serpentines to go to

work. Even in recent times, a

few decades ago, this small town was still a remote place as

paths on the western lake shore were too narrow to allow traffic to

pass to this

area. A tunnel system of

roads and parking terraces along the rocky west lake bank now

enables local people and visitors to get easy access to this

place.

Fluß Traun, 2005:

Fluß Traun, 2005:

Dieser Fluss durchfliesst die beiden Alpenseen Hallstätter See und

Traunsee. Der starke Traun-Durchfluss bewirkt eine relativ kurze

theoretische

Verweilzeit des Wassers in beiden Seen trotz der großen tiefen

Seebecken.

Stadt Bad Dürrenberg nahe der Stadt Halle,

2005:

Stadt Bad Dürrenberg nahe der Stadt Halle,

2005:

Sole wurde nicht nur für die Salzgewinnung im Mittelalter, sondern auch

für Heilzwecke und Wellness bis jetzt verwendet, wie es hier für die

Kurstadt Bad Dürrenberg (Deutschland) gezeigt ist. Auch die Orte in der

Nähe von Hallstatt (Österreich) waren beliebt für Wellness. Das Foto

zeigt Salzverkrustungen des Gradierwerkes. Eingefügtes Foto:

Gradierwerk mit Holzrahmenkonstruktionen, die mit Reisig von Prunus

spinosa

gefüllt sind. Die Sole wird von oben über die Reisigzweige verrieselt.

Mit der Verdunstung des Wassers lagern sich Salzkrusten auf dem Reisig

ab. Es wird gesagt, dass das Einatmen des Sole-Aerosols der Gesundheit

gut tut. Das Flanieren entlang eines Gradierwerks soll einem

Spaziergang am Meer gleichen.

Hallstatt is famous for

saltmining in the Austrian Alps. It is one of the oldest

salt

mining places around the world and was used for more than 7000 years.

It is suggested that the name ‘Hall’ does not refer to the word

‘salt’

of Celtic Language but to the technically newly introduced treatment

for salt crystallization commonly described in the language of High and

Middle German in the middle age, to the name of a processing plant,

where

underground brine is heated up

in a ‘salt pan’ (Sudpfanne,

Salzsiedepfanne, Saltzpan) to get solid salt (Stifter 2004/2005 R).

Simony wrote that the house with the salt pan was the heart of

Hallstatt , and that it was the working place for about 70-80 people

(“Das Pfannhaus ist das Herz Hallstatts,…”; page 52

in Grims 1996 R).

Such houses (Pfannhaus, Sudhaus, Siedehaus) with

‘Salzsiedepfannen’ were

frequently used to produce salt in the middle age in Europe, at places

where natural and artificially underground brine (in German ‘Sole’) was

available (e.g. the region around the city Halle in

Germany and

small

towns in the neighbourhood such as Bad Duerrenberg and Bad Koesen).

This

technique of salt production via underground produced brine was

efficient in the medieval period but

needed lots of firewood. High amounts of wood ash (in German ‘Asche’)

containing waste of salt compounds needed to be handled. In Bad

Duerrenberg,

a small town near Halle for example, the

waste of salt production by

encrustation of brine was transferred by small railway containers

(Loren, Güterloren)

to a salt mine waste tip (ash-salt tip, ‘Ascheberg

in Bad Dürrenberg’ at

‘Salinenstrasse’, road section between Ostrauer Strasse and Merseburger

Strasse, 51°18’2.1''N,

12°3'844.08''E). This salt mine tip is now moderately covered

by

vegetation.

Among other halophilic plants, dense stands of the yellow flowering

Horned Poppy (Glaucium flavum)

can be there found at the surface where

soil is mixed up with plate-shaped mineral salt crusts, the deposited

waste from salt pans. Different from Bad Dürrenberg in the low land,

in Hallstatt the area needed for the deposition of salt waste

was limited in the mountain environment. The ash-salt waste was

simply

dumped into the lake for hundreds of years. At the time of

the visits by Simony in 1866/68, one third of brine only was treated to

make salt in Hallstatt. The remaining brine was pumped via pipelines to

the village

Ebensee at Traunsee, to the ‘Sudwerk’ that was founded years ago, in

1607 (page 52

in Grims 1996 R).

In recent decades, the brine was not yet treated in

Hallstatt, but all transferred via pipelines to the plant in Ebensee at

lake Traunsee (see also on this website the effluence of mineral

industrial tailings in the recent period in Traunsee until the soda

production ended in 2005). Salt mining in

this alpine region played an important economic role but also

affected both the large lake ecosystems,

Traunsee and Hallstaettter See. The impact on Hallstaetter See is

shortly described in the following section about the limnology of this

lake. For Traunsee

S

see limnological details on the respective lake website.

Stadt Hallstatt am Hallstätter See, 2005.

Stadt Hallstatt am Hallstätter See, 2005.

Viele Häuser der kleinen mittelalterlichen Stadt sind in den steilen

Bergklippen am Ufer des Sees gebaut. Dieselben Häuser wie auf

den Foto links,

aber 2010 fotografiert.

Dieselben Häuser wie auf

den Foto links,

aber 2010 fotografiert.

Autos werden in dieser kleinen Stadt, einem Ort mit einer alten

Kulturgeschichte, „gut versteckt“. Der Verkehr wird über ein

Tunnelsystem entlang dem Rand der Stadt geleitet. Besucher parken ihre

Autos auf den Tunnel-Terrassen an den Klippen oder auf Parkflächen, die

einen etwa 15-minütigen Spaziergang entfernt vom Stadtzentrum liegen.

Menschen Zuhörend: 'Ja, es ändert sich so manches mit der Zeit, gerade heutzutage, wo vieles leider so arg kurzlebig ist. Oft denk’ ich so. Aber nicht, wenn ich hier auf der Terrasse steh’ und hinunter auf das kleine Hallstatt schau. Hier ist alles noch wie es vor Jahren war – zumindest über die Jahre gesehen, über die ich Hallstatt von Zeit zu Zeit besucht habe. Hier kann ich mich darauf verlassen, dass der Ort so aussieht, wie ich ihn schon oft geseh’n habe, am Ufer vom kristallklaren Hallstätter See, eingebettet in die Berge! Das ist Hallstatt! Wie oft war ich schon hier? Mit der Familie und mit Freunden! Ich weiß nicht, wie oft ich schon auf dieser Terrasse gestanden bin, wage es nicht mal dies grob abzuschätzen. Egal! Es zählt halt der Augenblick heute wieder einmal hier sein zu können, und das freut. Und heute bin ich hier mit Joe. Ich dreh mich vom See weg und schau verträumt hangaufwärts auf die weißen Häuser. Diese Häuser sind quasi mit dem Berg verwachsen! Wie werden sie wohl innen aussehen? Wer mich kennt, weiß wie gern ich dort mal einen Blick hineinwagen würde. Diese Häuser faszinieren mich immer wieder von neuem, sodass es jedes Mal ein Muss ist, sie nochmals zu fotografieren: mal sind sie von Schnee umgeben, mal im Regen, mal inmitten von Frühlingsgrün, in der gleißenden Sonne im Sommer oder eingeschlossen in den bunten Herbstfarben der Sträucher und Bäume. Und so fotografiere ich diese weißen Häuser auch heute wieder. Wunderschön! Wenn ich diese Häuser betrachte, kommt mir kaum in den Sinn, dass es für so manche Bergbaufamilie ganz sicher nicht leicht war an diesem Ort zu leben. Ich genieße den Blick hinunter auf den kleinen Markt von Hallstatt und sage zu Joe: „Die Aussicht ist herrlich! Und da oben, diese weißen Häuser, wie sie am Hang kleben, die haben es mir besonders angetan. ’s muss wohl leicht beschwerlich sein, seinen wöchentlichen Einkauf dorthin zu tragen?! ABER ich glaub’ mit einem zuverlässig funktionierenden Internetanschluss würde es mir gefallen dort zu wohnen. Das wär’ urnett! Joe, könntest du dir auch vorstellen hier zu wohnen?“ Joe antwortet nicht gleich, schaut vom Tal den Hang rauf und wieder hinunter auf den See und meint dann allmählich: „Also, ehrlich gesagt, für mich wär’ das nix. Ich würde hier nicht leben wollen. Der Ort ist überhaupt nicht gut zum Leben.“ Und während er dies sagt, schaut er leicht kopfschüttelnd über den See und das Tal dahin. „Da ist ja überhaupt kein Platz“, fährt er fort, „du kannst da keinen Getreideacker haben, kein Viehzeug, nicht mal Hühner! Gar nichts! Und überhaupt ist diese Bergwelt ja völlig ungeeignet für einen Weingarten.“ Und hier überzieht nun ein Lächeln sein Gesicht. Mit Augenzwinkern und abwinkender Hand fährt er munter fort: „Ja, ich würde hier meinen Weingarten vermissen! Samt dem alten Kirschbaum!“ „Ach komm, Joe“, sage ich, „wozu hat man einen Kirschbaum auf dem Weinberg?“ „Ich kann dir sagen, wozu ein Kirschbaum gut ist“, entgegnet Joe lachend. „Früher haben sie oft Kirschbäume mitten in die Weinberge gepflanzt. Warum? Sie haben die Kischbäume angebaut um Schutz zu haben. Man hatte Schatten um Mittag, wenn man eine Stunde mittags draußen auf dem Weinberg seine Jaus’n gegessen hat. Auch konntest du dich da bei Regen kurz unterstellen. UND - MAN KONNTE DAS PFERD ANBINDEN!!!!“ sagt Joe bedeutungsvoll mit leicht erhobenen Finger und mit nem Schmäh in den Augen fährt er betonend fort: „Und auch das Pferd braucht den Schatten. Und nicht zu vergessen, die Kirschen hatte man auch“, lacht er. „O.k., verstehe“ sage ich und lache mit! Ja, ja, die Zeiten, wie sehr sie sich doch geändert haben!’

Stadt Hallstatt und der

Hallstätter See,

2005.

Stadt Hallstatt und der

Hallstätter See,

2005.

Wie links aber leicht geschwenkte Ansicht,

2005.

Wie links aber leicht geschwenkte Ansicht,

2005.

Wie oben, aber 2007.

Wie oben, aber 2007.

Wie oben, aber 2007.

Wie oben, aber 2007.

.

Wie die beiden Fotos oben, aber 2010.

Wie die beiden Fotos oben, aber 2010.

Blick auf das Zentrum der kleinen mittelalterlichen Stadt und den See.

Das Foto ist von den Parkplatz-Terrassen aus aufgenommen, die vor

wenigen Jahrzehnten gebaut wurden. Wie die beiden Fotos oben,

aber 2010.

Wie die beiden Fotos oben,

aber 2010.

Blick auf den südlichsten Teil des Hallstätter Sees.

Der Ort Hallstatt, der in der Dachstein-Gebirgsregion der österreichischen Alpen gelegen ist, ist Teil des UNESCO-Weltkulturerbes. Diese Region wird hier als „Hallstatt-Dachstein Salzkammergut Kulturlandschaft“ bezeichnet. Eine detaillierte anschauliche Beschreibung dieses Standortes zusammen mit den sieben übrigen Welterbestätten in Österreich ist in Linder & Dröscher (2007, R) ausgeführt.

Rückblick aus dem Jahr 2013 auf frühere SeenUntersuchungen: Der Hallstätter See hat das Interesse der Wissenschaftler seit mehr als 160 Jahre angezogen.

we look back at the lake in year 2013: lake hallstaetter see has attracted lake scientists for more than 160 years

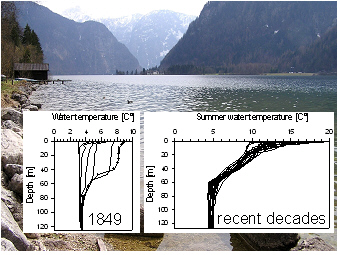

Hallstätter See, 2005:

Hallstätter See, 2005:

Links eingefügte Grafik - Tiefenprofile der Wassertemperatur im Jahre

1849 gemessen und veröffentlicht von Simony (1850). Die Linie mit

den Datenpunkten zeigt die Messdaten für den 31. August 1849. Die

anderen

Linien sind Messungen vom April, Mai und November desselben Jahres.

Rechts eingefügte Grafik - wie links, aber in den

letzten Jahrzehnten gemessen. Es werden hier nur die Werte für den

Sommer (Juli, August) gezeigt (Sommerdaten vom 'Bundesamt für

Gewässerökologie,

Fischereibiologie und Seenkunde').There

is hardly any other lake in the

Salzkammergut district that attracted naturalists for more than 160.

Early studies in Hallstätter See were mainly based on the temperature

depth profiles, and hence introduced limnological research in the

alpine region and in Austria. Probably, the most popular publication of

early measurements is by

Friedrich Simony released in 1850 and was

entitled ‘Die Seen des Salzkammergutes’ (‘The lakes of the

Salzkammergut district’). Grims (1996) describes Simony as a

naturalist, who was focused on land surveying of alpine mountains and

of

lake basins, but had also broad interests on glaciers, climatic ice

age, mineralogy & geology and botany & zoology.

Simony used a minimum

thermometer developed by Kapeller to measure

water temperature along vertical depths in the alpine lakes in the

Salzkammergut district (Simony, 1850). He wrote that eight minutes were

sufficient

enough for the thermal adjustment of the thermometer in the depth to

measure reliable data. According to his description, the replicated

measurements varied in the narrow range of 0.05 °C only. The

temperature

profiles of Hallstätter See by Simony are drawn in the left inset of

the right photo. The graph for summer measured on the date on

August 31

in 1849 is marked by plotting the individual data points, difficult to

confuse with lines of the other measurements in April, May and November

in 1849. This summer depth profile illustrates well that only the upper

stratum of the lake, the layer of about 40 (to 60) m is warmed up in

summer. This phenomenon of thermal

stratification is common in deep

lakes but was rather unknown at that time. With increasing air

temperature from spring to summer, the lake heats up successively from

the surface to deeper layers. This includes that (1) surface water of

the lake is getting warmer, (2) the thickness of the warmed up surface

layer increases consecutively (3) the thermocline 'grows up' and moves

downward into deeper layers (4) and the resistance against vertical

mixing increases (thermal stability of water column increases).

According to these thermal gradients, the water body of a deep lake

reaches a stabile thermal stratification in late summer. Further

descriptions about the thermocline, the metalinmion and the thermal

stability of water bodies is presented in the section ‘annual cycles by

heating and cooling of the water body’ on the website about lake

Mondsee S, and in the

section ‘Ammersee and Mondsee: two lakes but one

story’ on the website about lake Ammersee S. It

is worth

mentioning here,

that the thermal gradients in Hallstaetter See are partly interfered

with by

a stronger salinity gradient promoting a particular type of mixing, the

meromixis as it will be described under the section below.

Looking at recent temperature depth profiles for July and August

fromthe seventies to nineties shown in the right inset, it reminds us

that

the summer water surface

temperature may vary a lot among years in

Hallstaetter See. These summer temperature records ranged at the near

surface of 2 m from 9.7 to 18.5 °C and at depth of 9.5m from

9.5 to

13.15. The individual measurements on August 31 in 1949 by

Simony at

2 and 9.5 m refer to a bit lower temperatures, namely to 9 and

7.3 °C

respectively. Taking into account the different equipment that was used

about 160 years ago, the temperature records by Simony should be

interpreted with caution when compared with recent temperature data

sets. Besides this uncertainty, however, one may say that Simony has

just measured in a year of a particularly cold summer. Others might

claim that warming by climate change might be most responsible that the

temperature measured by Simony is rather an outlier than within the

range of statistical deviation from the expectation when compared with

recent times.

According to monthly means of surface temperature in August, measured

in Hallstatt, the temperature tended indeed to increase by about 1.326

degree over a period of 100 years (1901-2000), namely from 14.9 °C to

15.74. During this period, in 54 years occurred a negative

anomaly in August, which was on average –1.15 °C. In the remaining 46

years, a positive temperature anomaly was recorded and here the mean

temperature in August was on average 1.38 °C warmer than expected by

the

long-term trend. In extreme years, the surface temperature in August

could be even 3.28°C lower or 4.16 higher, respectively. These few

numbers illustrate the range of temperature variation in August in

individual years during the 20th century. It shows that the

measurements by Simony are not that extreme as at first glance they

might have seemed when comparing the temperature depth profiles of both

discussed graphs. Climate warming, however, does not follow necessarily

linear trends over too long periods and therefore, the trend estimated

for the 20th century cannot be simply used to calculate backwards what

the usual temperature in August 1849 would have been. For this reason,

the question is not yet answered here to what extent climate warming or

an extreme cold summer or simply the uncertainty caused by the use of

different instruments was most responsible that Friedrich Simony had

written in his notes the numbers of a relatively cold-water body in

August 1849. The climate

response on the WHOLE water body of Hallstaetter See will not

be described on this page.

Evidence for significant

DEEPWATER warming at depths of 80, 100 and

120m in Hallstaetter See, however, was found in a recent study (Table

2 and Fig.2 I

in Dokulil et al.

2006 R).

These statistically significant

trends in Hallstaetter See were in concert with other lakes of the

Salzkammergut district and also lakes across Europe. Other deep alpine

lakes in Austria, however, seemed to respond more closely to global

climate signals than Hallstaetter See (see the correlation with the

NAO-index

integrated

over the period January to May in Table

4

and Fig.3 in Dokulil et al.

2006 R;

NAO signal see also Mondsee S

and Ammersee S). The reason for

the individual lake response of Hallstaetter See can be attributed to

the low wind-exposure of the alpine valley lake basin, which extends

from north

to south (see page 2789 in

Dokulil et al.

2006 R).

It is further argued, that

Hallstätter See is locally surrounded by a cold environment as the lake

receives on average about five hours less sunshine than other alpine

lakes in it’s neighbourhood. This situation thus counterbalances the

impact of global warming and explains why the significant increase of

deepwater warming is not that strong compared to other neighbouring

lakes

(e.g. see for lake Traunsee Table 2

and Fig.2 J in Dokulil et al.

2006 R).

Another reason for the individual lake response to climate signals can

be found when considering the study by Ficker et al. (2011 R),

even the

impact of climate was not mentioned in their analysis. They observed

two water-mixing regimes that occurred alternatively from time to time

in recent decades in Hallstaetter See, the meromixis and holomixis. The

shifts among the both mixing regimes were linked to the many ups and

downs of water density in the salt-mining lake, namely by the sudden

increase of chloride concentrations after every brine spill, on the one

hand, and a decrease by washing-out on the other (Fig.2

in Ficker et al.

2011 R).

While periods of high chloride were associated with

meromictic mixing, periods below a certain threshold concentrations of

chloride referred to holomixictic mixing. The toggled two mixing

regimes that were mainly linked to fluctuations of chloride

concentration (and not primarily to temperature effects) might thus

also explain the more individual

lake response to climate signals (NAO)

in Hallstaetter See than compared with other deep alpine

lakes.

Two studies - by Liburnau (1898) mainly about zooplankton and by Keissler (1903) about phyto- and zooplankton – describe very early the planktonic species in lake Hallstaetter See. Keissler used an Apstein plankton net to take samples, and hence he describes only large or colonial phytoplankton species as e.g. the green algae Staurastrum paradoxum, Sphaerocystis schroeteri and Botryococcus braunii, the diatoms Cyclotella comta and Asterionella formosa, the chrysophyte Dinobryon divergens and the dinoflagellates Ceratium hirundinella and Peridinium cinctum. The size of these phytoplankton forms is larger than (30 -) 50µm. Large species are, however, usually much less abundant in alpine lakes than small species. It could be shown for other alpine lakes in Austria and in Switzerland, that the small cell size fraction of only 0-10 µm contributes more than 50% to the total chlorophyll concentration of phytoplankton (Teubner et al. 2001 R). In this way, the samples by Keissler certainly missed main components of phytoplankton. Despite these uncertainties, Kreissler is probably right to emphasize that the abundance of the species found in net phytoplankton from Hallstaetter See was in particular low when compared with those of other lakes in the Salzkammergut district. He also stated that phytoplankton was only found in the upper 60 meters, which corresponds to the warmed up top layer described by Simony. Taking depth integrated net samples, Keissler also measured the water transparency (see details in the section below).

Meeresbälle,

2013:

Meeresbälle,

2013:

Aus Fasern gebildete Meereskugeln sowie Muscheln am Strand des

Mittelmeeres. Die Form und das Aussehen dieser Bälle ähnelt den Kugeln,

die im See Hallstätter See gefunden werden. Sie werden hier nach Morton

als “Die Hallstätter Seekugeln“ oder “Lärchennadel-Bälle“

benannt.

Solche Seekugeln wurden auch von anderen Seen in Österreich

beschrieben.  Meeresbälle, 2013:

Meeresbälle, 2013:

Wie das Foto links, aber als Detailansicht. Diese Kugeln vom Meer

schauen weniger grob gefasert aus als die der Seen, die durch Nadeln

aufgebaut sind.

The fibrous spherical to ellipsoid formations found in the littoral zone and on the shore of Hallstätter See are perhaps the greatest curiosities for people enjoying nature and lakes, and were described first for Hallstaetter See by Friedrich Morton. He called these fibre-lake-balls ‘Die Hallstätter Seekugeln‘ ('The lake balls from Hallstaetter See', Morton, 1924 R R), and in a later publication ‘Lärchennadelnbälle’ (‘Balls made by larch needles’). These balls are processed from needles of Larix decidua. Morton wrote that he found them most abundant in shallow shore areas of Hallstätter See, where the needles built a dense layer of about 10 centimetres on littoral sediment washed on the waves. The intertwining of plant fibres of Larix needles begins on small pieces of rhizomes e.g. of Carex from the littoral or other material of rough surface. The initial small balls grow up further in the moved shallow water. According to Morton, these balls were common on the south-east shore of the lake, between the inlet of River Obertraun and the village Winkl; and were also found but more rare along the west shore between ‘Lahn und dem Landungsplatze im Markte’. These natural fibre marbles actually might have fascinated him, as he published a series of seven (!) short notes on ‘Lärchennadelbälle’ found in Hallstätter See (the first was published in 1934, see all references in Müller & Werth, 1982 R) and one publication for a lake nearby, the Offensee (balls were found close to the outlet of stream Offenbach; Morton, 1964 R). Such fibrous balls (‘Seebälle / Meeresbälle’ ; ‘sea balls / marine balls’) seem to be more common in the Mediterranean Sea than in lakes (see the two photos above). Sea balls are built by other plant fibres than Larch needles, but look very like the lake balls, which are shown in photos published by Morton 1964 R.

anzeichen einer ökologischen unstimmigkeit in diesem salzhaltigen see: Ist das kristallklare Wasser des Hallstätter Sees tatsächlich ein Ausdruck eines gesunden Ökosystems?

the gap in this saline aquatic ecosystem: is the crystal-clear water of Hallstaetter See indeed the signature for a healthy environment?

Hallstätter See, 2005:

Hallstätter See, 2005:

Das kristallklare Wasser verspricht auf den ersten Blick eine hohe

Wasserqualität dieses Alpensees: Zeigt es hier zugleich

den Status

eines uneingeschränkt gesunden Ökosystems an?

One may argue that water transparency

is the

best parameter describing water quality of inland waters. According to

Keissler (1903), the Apstein plankton net was visible up to 3 to

6 m

below the water surface during

sampling from July to September 1902 in Hallstaetter See (the average

was 4 m, 12 measurements). The standard

measurement with a Secchi disk (see preface S) in

recent

decades

revealed a

Secchi transparency depth of about 4 to 5 m in

June and

August in this lake, respectively (ranging from 1.5 to 7 m,

see

Fig.8 in Dokulil

& Teubner

2002 R). The water

transparency depends mainly on the amount of

floating particles in the water column, which are described as

inorganic and organic suspended solids. The latter are mainly phyto-

and zooplankton that are most abundant during growing season (see

seasonal development of phytoplankton on the page about

Bergknappweiher S).

When Secchi depth is measured in winter or before the

spring peak development, the values can be even higher. In the case of

Hallstaetter See the Secchi depth is early spring about 8 m, ranging

from 7-10 m (see data for March in Fig.

8 in Dokulil

& Teubner

2002 R).

Such

crystal-clear water, as found in Hallstaetter See, seems to be very

attractive for tourists to visit and enjoy the alpine lake region. Only

in few lakes in the Salzkammergut district, as e.g in lake Attersee S

(see Fig. 8 in Dokulil

& Teubner

2002 R)

is the water transparency even higher

than in Hallstaetter See.

Das Ostufer vom Hallstätter See,

2005:

Das Ostufer vom Hallstätter See,

2005:

Der beliebte Wanderweg “Ostuferweg“ geht durch Wiesen, Obstgärten und

Wälder entlang dem Seeufer. Das Ostufer vom Hallstätter

See, 2001:

Das Ostufer vom Hallstätter

See, 2001:

Streuobstwiese mit frisch gefallenem Schnee zu Ostern (April) am

Seeufer. Rechtsseitig ist ein Bootshaus zu sehen.

Das Ostufer vom Hallstätter See,

2001:

Das Ostufer vom Hallstätter See,

2001:

Traditionelle alpine Holzhäuser von Streuobstwiesen umgeben liegen nahe

der Wasserkante vom Seeufer.

Das Ostufer vom Hallstätter See,

2000.

Das Ostufer vom Hallstätter See,

2000.

Blühende Sommerwiese mit Glatthafer (Arrhenatherum

elatius)

und Habichtskraut (Crepis

spec.) unweit vom Seeufer.

Das Ostufer vom Hallstätter See,

2005.

Das Ostufer vom Hallstätter See,

2005.

Nachhaltige Tierhaltung auf kleinen Bauernhöfen befindet sich am Ufer

von diesem Alpensee. Das Ostufer vom Hallstätter

See,

2001.

Das Ostufer vom Hallstätter

See,

2001.

Wälder aus Buchen (Fagus sylvatica)

und Fichten (Picea

abies)

erstrecken sich entlang dieses Alpensees.

In view of biota living in the lake water body, water transparency refers to the underwater light climate that controls the growth of microbial primary producers (e.g. algae). The Secchi depth of about 4.5 m in summer and 8 m in early spring in Hallstaetter See corresponds to an euphotic depth covering about the top 15 and 27 m, respectively (see also underwater light climate described on the page for Mondsee S and Traunsee S). The epilimnetic layer (see depth profiles for summer water temperature shown in the figure above) might thus largely exceed the euphotic layer. The proportion between the concentration of chlorophyll-a (Chl-a), which is used as a rough estimator for biovolume of phytoplankton, and the concentration of total phosphorus (TP) in Hallstaetter See, is relative low when compared with the Chl-a:TP proportion in other alpine lakes of the Salzkammergut district, like Attersee, Mondsee, Traunsee and Wolfgangsee (see Fig. 6.54 in Dokulil et al. 2000). In other words: It seems that the phytoplankton yield is much less than might be expected from the total phosphorus pool size in Hallstaetter See (see also Fig. 8 in Dokulil & Teubner 2002 R). Even though the water looks crystal-clear the surprisingly low phytoplankton biomass raises questions about the ecosystem integrity or the ecosystem health. One reason among others could be perhaps the mismatch between the euphotic depth and mixing depth described for this lake before. Another impact might be due to the large discharge by the River Traun, which is passing the lake Hallstaetter See (see the plume horizon of the River Traun identified in the top 6.5 to 20 m along the 140 m depth profile in Traunsee S). Salinity, however, might not simply explain the unexpected low biovolume of phytoplankton as values for conductivity and chloride are much lower in lake Hallstaetter See than in lake Traunsee. Further, the low nutrient concentration, in particular of phosphorus, would not contribute to understanding the low phytoplankton development in Hallstaetter See, as phosphorus concentration in Attersee is even much lower than in Hallstaetter See but the amount of phytoplankton biovolume relative to the total phosphorus pool is commonly higher in Attersee than in Hallstaetter See. As lake Attersee S is an ultra-oligotrophic lake and as the lake was not used for salt mining at all, phytoplankton assemblages of this lake occur in a pristine alpine ecosystem. In view of the European Water Framework Directive lake Attersee is thus described as reference ecosystem for the Austrian alpine lakes in the Salzkammergut district. For many reasons, however, coarse and simple monitoring measurements in Hallstaetter See in comparison to other mentioned alpine neighbouring lakes, that strictly satisfy the rules of European Water Framework Directive, do not provide a satisfying perspective to understand the complexity or functioning of these ecosystems. A subtler approach, however, seems to be more appropriate to answer the question of unexpected low biomass of primary producers in Hallstaetter See. An advanced ecosystem study might cover the utilization and turnover of nutrients (in particular of phosphorus, see small scale phosphate acquisition on the page preface S), the potential growth inhibition of biota and the match or mismatch of allocation pattern among various planktonic organisms - bacteria, cyanobacteria, algae and the many types of zooplankton -, and also fish. Such a more detailed study about the interaction of aquatic organisms with their environment along depth layers would be essential to answer the question how efficiently nutrients can be exploited by biota in Hallstaetter See.

cited References: about hallstaetter see

Ficker, H., Gassner, H., Achleitner, D. & R. Schabetsberger. 2011. Ectogenic Meromixis of Lake Hallstättersee, Austria Induced by Waste Water Intrusions from Salt Mining. Water Air Soil Poll, 218: 109-120. FurtherLink

Schmidt, R., Roth, M., Tessadri, R. & K. Weckström. 2008. Disentangling late-Holocene climate and land use impactson an Austrian alpine lake using seasonal temperature anomalies, ice-cover, sedimentology, and pollen tracers. J Paleolimnol, 40: 453–469. FurtherLink

Linder, W. & U. Dröscher. 2007. Welterbe für junge Menschen – Österreich. Ein Unterrichtsmaterial für Lehrerinnen und Lehrer (Sekundarstufe I und II). Österreichische UNESCO-Kommission, Wien. 114 pp. FurtherLink

Dokulil, M. T., Jagsch, A., George, G. D., Anneville, O., Jankowski, T., Wahl, B., Lenhart, B., Blenckner T. & K. Teubner. 2006. Twenty years of spatially coherent deep-water warming in lakes across Europe related to North-Atlantic Oscillation. Limnol Oceanogr, 51 (6): 2787-93. doi:10.4319/lo.2006.51.6.2787 OpenAccess

Dokulil, M. T., Teubner, K. & A. Jagsch. 2006. Climate change affecting hypolimnetic water temperatures in deep alpine lakes. Verh Internat Verein Limnol, 29: 1285–88. Look-Inside

Gassner, H., Zick, D., Bruschek G., Frey I., Mayrhofer,K. & A. JAGSCH. 2006. Die Wassergüte ausgewählter Seen des Oberösterreichischen und Steirischen Salzkammergutes 2001-2005. Schriftenreihe des BAW, Band 24, Wien. FurtherLink

Stifter, D. 2004/2005. Hallstatt – In eisenzeitlicher Tradition? Kataloge des Oberösterreichischen Landesmuseums N. F., Austria: pages 229–240. FurtherLink

Dokulil, M.T. & K. Teubner. 2002. The spatial coherence of alpine lakes. Verhandlungen der Internationalen Vereinigung für Theoretische und Angewandte Limnologie (Verh. Internat. Verein. Limnol.) 28, 1-4. Look-Inside

Dokulil, M.T. & K. Teubner. 2002. Assessment of ecological integrity from environmental variables in an impacted oligotrophic alpine lake: Whole lake approach using 3D-spatial heterogeneity. Water Air Soil Poll, Focus , 2: 165-80. Look-Inside FurtherLink

Jagsch, A., Gassner, H. & M.T. Dokulil. 2002. Long-term changes in environmental variables of Traunsee, an oligotrophic Austrian lake impacted by salt industry, and two reference sites, Hallstättersee and Attersee. Water Air Soil Poll, Focus , 2: 9-20. FurtherLink

Teubner, K., Sarobe, A., Vadrucci, M.R. & M. Dokulil. 2001. 14C photosynthesis and pigment pattern of phytoplankton as size related adaptation strategies in alpine lakes. Aquat Sci 63: 310-25. doi:10.1007/PL00001357 Look-Inside FurtherLink

Dokulil, M., Teubner, K., H. Gollmann, S. Wanzenböck, C. Skolaut & Ines Lemberger. 2001. Modul 6: Quantitative Algenökologie. pages: 376-429; In: Projektstudie Traunsee - Auswirkung der SOLVAY-Emissionen auf die ökologische Funktionsfähigkeit des Traunsees, 574 pages.

Grims, F. 1996. Das wissenschaftliche Wirken Friedrich Simonys im Salzkammergut. Stapfia, 43: 87-96; also cited as: 1996, Kataloge des Oberöstereichischen Landesmuseums N. F. 103: 43-71. FurtherLink

Müller, G. & W. Werth. 1982. Limnologische Literatur für Oberösterreich, Austria (1892-1982). Oberösterreichischer Musealverein - Gesellschaft für Landeskunde, JOM, 128 a1: 255-280. FurtherLink

Morton, F. 1934. Ein neuer Fundort von Lärchennadelnbällen am OffenseeJahresbericht des Oberösterreichischen Musealvereins, 109: 454-457. Arbeiten aus der Botanischen Station in Hallstatt,252: 454-457 FurtherLink

Morton, F. 1934. Die Lärchennadelnseebälle des Hallstätter Sees. Erste Mitteilung. Arch Hydrobiol, 27: 609-612.

Morton, F. 1924. Die Hallstätter Seebälle. Vorläufige Mitteilung. Jahresbericht des Oberösterreichischen Musealvereins, Austria, 303-305. also: Kataloge des Oberöstereichischen Landesmuseums N. F. FurtherLink

Keissler, v.K. 1903. Über das Plankton des Hallstätter Sees in Oberösterreich. Verhandlungen der zoologisch-botanischen Gesellschaft Wien, Austria, 53: 338-48. FurtherLink

Liburnau, L. 1898. Der Hallstätter See, eine limnologische Monographie. Mitteilungen der geographischen Gesellschaft Wien, Austria, 41: 218 pp; about Protozoa, Rotatoria, Crustacea, Mollusca, Diptera & Trichoptera

Simony, F. 1850. Die Seen des Salzkammergutes. Sitzungsberichte der mathematisch naturwissenschaftlichen Classe der kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften, 24 pp.